Most people associate promotional communications with the consumer marketplace. Companies create and send these communications as marketing messages, or a call to action, because they want consumers to purchase or utilize their product.

The healthcare industry also uses promotional communications as marketing messages to alert patients and members of new products or services. Maybe the local healthcare system has opened a new cardiac center and wants to attract new patients. Or simply wants to promote the brand and mission of the overall healthcare system.

What if we used promotional communications to target chronically ill patient populations? Can we utilize the same approach and strategy companies use when targeting the consumer marketplace?

This post’s purpose is to examine the opportunity and issues when targeting chronically ill patient populations with promotional communication tools that focus only on promoting health literacy and reducing healthcare usage.

Please give me what I want

Promotional communications have been around since the invention of printing presses. But, until the launch of digital printing presses, the communications were static – meaning there was no variable data.

This doesn’t mean every consumer received the exact same communication. Even before the internet and mobile phones, data was gathered on consumer interests and purchasing habits. Credit card companies watched your purchases. Payers gathered claims data. Consumers with similar interests or backgrounds were targeted as groups with specific static messaging. As you might imagine, the response rates were very low.

Real change started with the 1990 launch of digital printing presses like the Xerox DocuTech 135. Now there was a possibility of personalizing promotional communications with information specific to an individual consumer. The level of personalization was still basic, but the following 20 years delivered revolutionary innovation and progress in three distinct areas:

- Communication technology: I wrote about this in my most recent post. The quality of digital printers has gone up and the cost has gone down. Full color is now the norm. You also have a wide variety of communication channels beyond print like web, mobile phone and email.

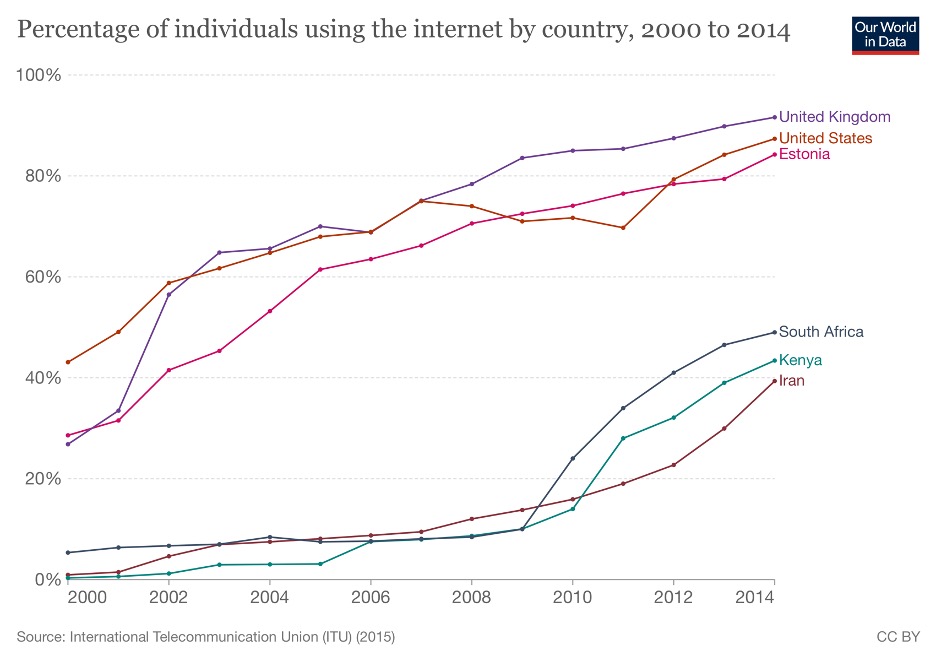

- Data: Widespread use of the Internet has gathered incredible amounts of data on individual consumers’ preferences and purchasing history (see chart below)

- Data Analysis: The power of data analytics has been unleashed, giving marketers a far better idea of consumer behavior.

In 2000, 50 percent of people in the United States were accessing the Internet. By 2014, the figure was approaching 90 percent. This Internet usage (and the tools analyzing it) is creating a world where marketers have detailed profiles on individual consumers and use them to create highly personalized promotional communications. That’s why their response rates continue to increase. Twenty years ago, a response rate less than one percent was common. Now you have promotional campaigns exceeding ten percent response rates.

Response rates aren’t the only measure

Higher response rates are good but return on investment (ROI) is a better measure of communication campaign success. How much does the communication campaign cost versus the return (increased sales or some other key measure)? For some high value situations, a small improvement might completely justify the campaign cost. In other low value situations, doubling the response rate might be a complete failure. The point is you can justify more of these campaigns where small improvements generate huge returns. And what better example do we have than chronic illness? Small improvements in the health of chronically ill populations have the potential to deliver huge savings.

Healthcare lags

The healthcare industry has sent out promotional campaigns for decades. But, compared to the consumer marketplace, healthcare has lagged behind significantly for a variety of reasons.

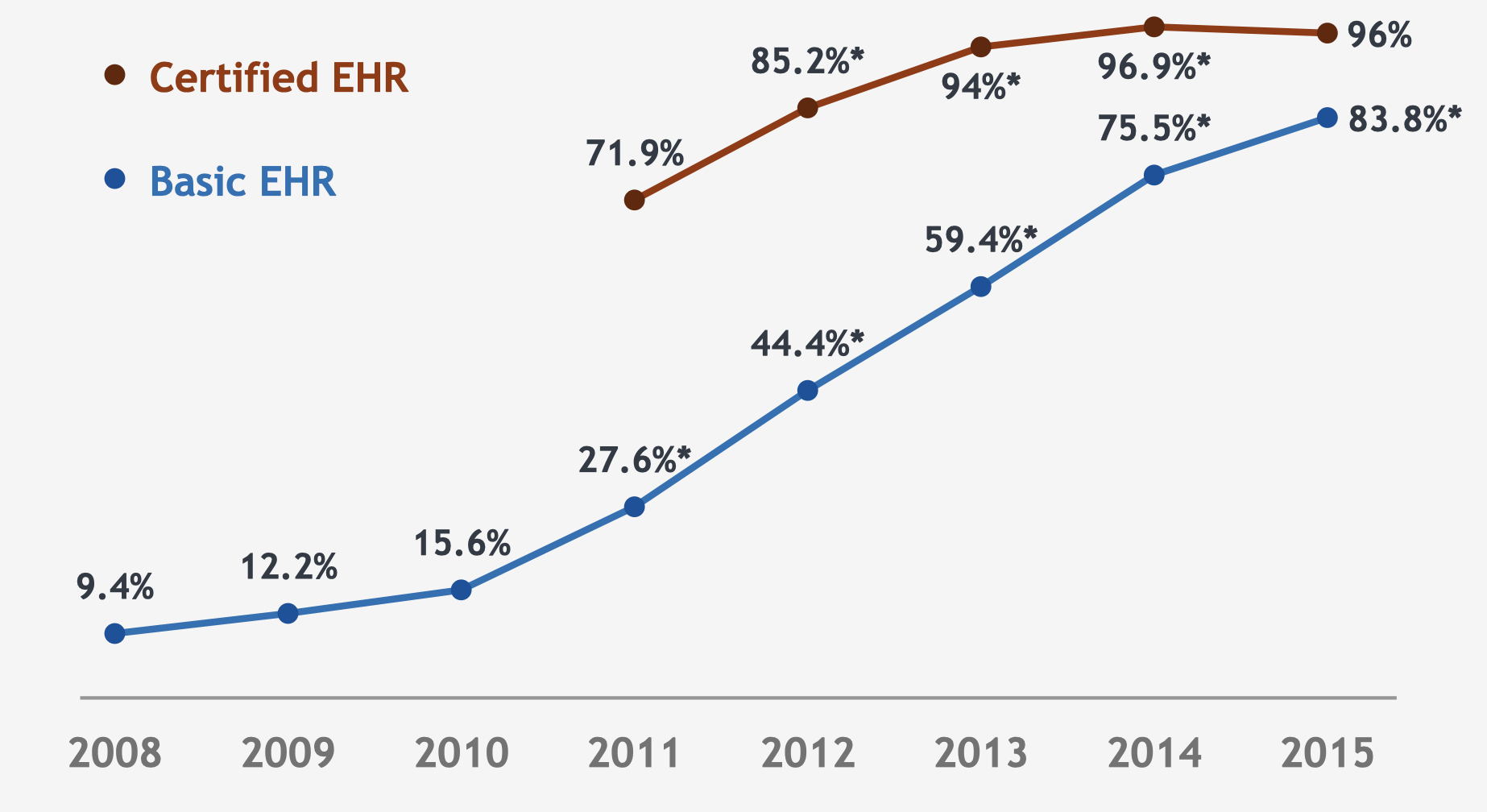

Delay in Digital Data: Implementation of Electronic Health Records Systems (EHR) didn’t really start until 2010 or so (see below). Since then, the widespread adoption of EHR has enabled electronic storage of patient data along with a wide variety of tools to access it. In comparison, the consumer market has been gathering huge amounts of digital data since the adoption of the Internet (see graph above). That’s a huge head start.

Source: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

Wrong Data: Most EHR healthcare data is clinical, not consumer-oriented non-clinical data. This works well for treating illness, but we need the non-clinical data on education, language, culture, and socioeconomic barriers to treatment.

Unfortunately, EHR systems don’t readily store this type of data. Why would they? The original intent of EHR was to digitize clinical information in support of clinical activities. Communications were an afterthought. As a result, their communication capabilities are more basic with static communication printed out at the point of need.

Payers and EHR vendors have tried to address this with population healthcare platforms which include tools for managing chronically ill patient populations. But most are focused on identifying undiagnosed chronic conditions or operational reporting. Some attempt to add on third party or other communication capabilities, but they don’t have the power of consumer models. As a result, many communications from these platforms are limited in their ability to persuade or address barriers to treatment.

Fragmentation: The same issues in we have in clinical fragmentation exist in communications.

- Fragmented Delivery: Communications are sent by a variety of clinical providers and payers with their own platforms.

- Fragmented Data: The limited, non-clinical patient information we do have is stored on a variety of systems without connectivity.

Who do we target?

Important work is taking place to address the fragmentation of care and clinical data affecting our ability to successfully treat chronically ill patient populations. However, we need to do more.

First, we should target chronically ill patient populations with data gathering programs that document non-clinical barriers to health literacy. This is key information on education, language, culture, and socioeconomic barriers to health. Gathering this data will allow analysis to generate actionable insights we can use to fine-tune communications and promotions targeting chronically ill patient populations. In a perfect world, this data would be part of the longitudinal patient record, accessible to all providers.

Second, we should create a national program to test promotional communications targeting chronically ill patient populations. This should focus on testing imagery and messaging to increase overall health literacy. Results should be shared with all payers and providers so they can modify their communications. If we rely on individual payers or providers to fund this work, it won’t be broadly shared as the funding organization will see it as a competitive advantage.

No easy out

The people who manage promotional communications targeting consumers don’t accept all consumers are similar. They don’t assume all people will respond to the same message. If anything, the vast amount of data and the tools analyzing it are creating a world where you can drill down to individuals and create highly targeted and effective one-on-one communications.

This approach is at odds with clinical treatment of chronically ill patients. First, their symptoms and treatment paths are remarkably consistent. Second, providers are working hard to standardize clinical care to make it more measurable and reproducible.

Unfortunately, patients’ interests and backgrounds are not consistent. They grow more diverse with each passing year. Standardizing communications won’t work. It’s time to treat chronically ill patient populations as consumers of healthcare. And gather the information we need to target them with personalized communications, addressing their unique barriers to improved health literacy and care.

There is no question this effort will be expensive. However, the current cost of chronic illness is so great, even small improvements in health literacy – or removing socioeconomic barriers to care – will yield significant savings.

No Comments